|

|

|

01 |

Montagues and Capulets |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

05:19 |

|

|

02 |

The Child Juliet |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

04:08 |

|

|

03 |

Folk Dance |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

04:21 |

|

|

04 |

Mask |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

02:16 |

|

|

05 |

Friar Lawrence |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

02:45 |

|

|

06 |

Dance |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

02:01 |

|

|

07 |

Romeo & Juliet |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

07:55 |

|

|

08 |

Death of Tybalt |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

04:41 |

|

|

09 |

Romeo at Juliet's Before Parting |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

08:13 |

|

|

10 |

Dance of the Antilles Girls (Suite 2, No. 6) |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

02:11 |

|

|

11 |

Romeo at the Grave of Juliet |

Cleveland Symphony Orchestra |

|

|

06:12 |

|

| Location |

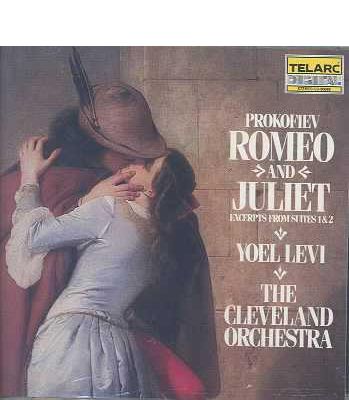

Telarc Collection |

| Disc 1 |

: CD-80089 |

|

| Studio |

Severance Hall, Cleveland, Ohio |

| Catalog |

CD-80089 |

| Packaging |

Jewel Case |

| Recording Date |

10/24/1983 |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

| Classification: |

TELARC CLASSICAL |

|

| Composer/Artist |

Sergei Prokofiev (1891 - 1953) |

|

|

It took Tchaikovsky to show Russian audiences that music for

the ballet did not need to be of the mild, self-effacing ilk

that had been the norm for centuries. But the two Russian

composers who were to learn Tchaikovskys lessons best, and

who were to add their own brilliant manifestos to the

provocative genre, both built their reputations outside of

their native land. Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev made

their marks as collaborators for the dance while working in

Western Europe with the great Diaghilev, his Ballet russes,

and the master choreograohers and scenic designers in that

legendary entourage.

It has been claimed that Prokofiev, the virtuoso pianist,

longed to concentrate his creative energies on opera, which

he is said to have considered the highest of art forms. Be

that as it may, by the time the 41- year-old composer

resettled in Russia after fourteen years abroad, he was

known across the Continent and in America as a purveyor of

his own brittle, exotic works for the piano, and as a

composer of ballet scores, including Chout, Le pas dacier,

The Prodigal Son, and Sur le Borysthène (now the Dnieper

River, in the Ukraine).

Soviet cultural policies aside, it is not at all surprising

that, having decided to go home, Prokofiev had to

reaccilimate himself to his countrymens ways. The composer

wrote in his Autobiography that the Russians ""like long

ballets which take a whole evening; abroad the people prefer

short ballets... This difference of viewpoint arises from

the fact that we attach greater importance to the plot and

its development; abroad it is considered that in ballet the

plot plays a secondary part, and three one-act ballets give

one the chance to absorb a large number of impressions from

three sets of artists, choreographers and composers in a

single evening.""

Still, that does not fully explain why Prokofiev, dealing

with the Kirov Theater to present a new ballet score,

decided on Romeo and Juliet. Surely he knew Berlioz

dramatic symphony, Gounods opera and, more crucially,

Tchaikovskys overture-fantasy, all on the same story - but

precedents, however effective, are not enough to justify

what appears to have been the composers conscious decision

to move out of the musical arena in which his career had

been built.

His motivation was musical. In his Autobiography, Prokofiev

listed the four primary elements in his own musical style:

the classical, the modern (including what he called

""crudity""), the motoric or toccata, and the lyrical. ""As

time went on;"" he wrote, ""I gave more and more attention to

(the lyrical) aspect of my work."" The more he considered the

possibilities of a Romeo and Juliet ballet score, the more

he saw that such a project would allow him to capitalize on

these lyrical aspects, as well as to incorporate the other

elements which had been integrated into his creative

signature. He would have to face criticism for mixing such

seemingly disparate elements as ""crudity"" and classicism;

only the more astute listeners realized upon first hearing

the ways in which Prokofiev had unified his lengthy score

through the use of recurring motifs - not merely themes to

signify the characters arrivals onstage, but motifs to

suggest emotions, changing situations and fate. There are

many who contend that Prokofievs Romeo and Juliet is, quite

simply, the greatest ballet score ever written.

The course of this Romeo and Juliet did not run smooth. The

Kirov Theater changed its collective mind about the project,

so Prokofiev took his idea to Moscows Bolshoi Theater,

where he was led to expect a premiere late in 1935. The

composer delivered the score at the end of the summer of

that year, only to be told that he had written music that

was impossible to dance to, and to have his contract broken.

Furthermore, Prokofiev had offended the sensibilities of

academia. In the belief that ""li

Companies, etc.

Phonographic Copyright (p) – Telarc Records

Copyright (c) – Telarc Records

Manufactured By – Matsushita Electric Ind. Co., Ltd.

Recorded At – Severance Hall

Credits

Art Direction – Ray Kirschensteiner

Edited By – Elaine Martone

Engineer – Jack Renner

Photography By [Cover Photo] – John Watt (7)

Producer – Robert Woods (2)

Notes

Very early Japan-for-US pressing with hand etched matrix numbers in the mirror ring.

Issued in a smooth sided jewel case with a gray tray with "Patents pending" on the back.

Recorded in Severance Hall, Cleveland on October 24, 1983

℗ © 1984 TELARC® RECORDS

Made in Japan